Edgar Allan Poe gave American writers permission to plumb the subterranean depths of human depravity and transform it into art. This may sound obvious, but it’s worth remembering—on his 208th birthday—that Poe composed his pioneering gothic stories for a Yankee audience. Europeans already indulged in the profane poetry of Charles Baudelaire (Poe’s French translator) and attended the bloody spectacle of Grand Guignol theater so it’s no wonder they embraced the graveyard poet before America, whose prudish shores had never read anything like him.

Now, of course, his stories and poems are ubiquitous. Roderick Usher and Annabel Lee are as much a part of the American psyche as Tom Sawyer and Hester Prynne. The man himself inspires devotions of all kinds. A Japanese writer gave himself the phonically-symmetrical pen name Edogawa Rampo. (Speak it out loud). The Baltimore football team is named after his most famous piece of verse. And for the last fifty or so years, on January 19, a hooded stranger known as the Poe Toaster has left three roses and a bottle of cognac at his gravesite. (The tradition seemed to end in 2009.) The name Poe is synonymous with ominous corvidae, decaying corpses, murder (both human and feline), slow-boiling revenge, premature burials, and a rampaging orangutan wielding a shaving razor—that last one, fans know, is the culprit (spoiler alert!) of “The Murders in the Rue-Morgue,” one of three tales concerning, what Poe called, ratiocination. The modern world calls it detective fiction. Give thanks to Edgar for his invention of the first literary sleuth, Auguste Dupin; without this Parisian detective, it’s safe to say there might not be a Sherlock Holmes.

But while the invention of Horror and Detective fiction remain the tent-poles of Poe’s reputation, the man’s intellectual scope as a writer stretched far beyond the macabre. One of his primary obsessions was the nature of the self, which he explored in stories such as “William Wilson,” where a man hunts down and kills his doppelganger, and “The Man of the Crowd,” which is about a stranger who can only exist amid a seething urban mass of humanity. He wrote political satire (“Mellonta Tauta”), science fiction (“Hans Phall”—about a trip to the moon in a hot air balloon), and straight-up fantasy (“A Tale of the Ragged Mountains”). And a good number of his lesser known tales, such as “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether” and “Some Words with a Mummy,” display a bizarre sense humor.

Perhaps the oddest result of his fecund imagination was a late career text entitled Eureka, a homegrown, not-wholly-scientific theory of the universe in which he described—predating Georges Lemaitre—the Big Bang theory. Famously, Poe’s work did not find the wide readership he so desired. Only “The Raven” brought him real fame, a poem of which Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “I see nothing in it.” American letters in the 19th century was, it could be argued, a cloistered community of privileged men, and Poe’s poverty and a proclivity for the drink gave him a reputation as a bitter outsider. (Although he won the admiration of Dickens and Hawthorne.) His nasty temper also produced a few hatchet job reviews. He trashed Emerson’s ideas about Nature, accused Longfellow of plagiarism, and dismissed Washington Irving as “much over-rated.”

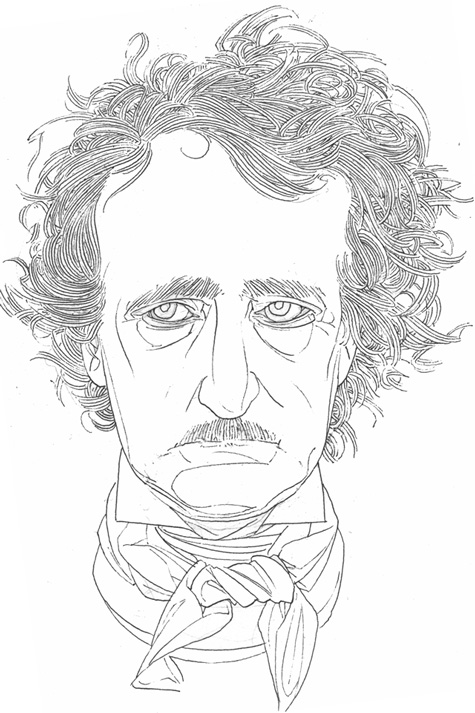

In the end, Poe was an author saved by his readers, both European and American. What survives is not only his writing, but a cultural idea of the man himself as brooding, tortured romantic. John Allan, Poe’s foster father, perhaps said it best:

“His talents are of an order that can never prove a comfort to their possessor.”

Happy Birthday, Eddie!

This post originally appeared on January 19, 2013.

Matthew Mercier is a writer and storyteller whose work has appeared in The Mississippi Review, The Brooklyn Rail, Glimmer Train, and The Raven Chronicles. He currently teaches at Hunter College. He’s worked as a youth hostel manager in New Mexico, packed salmon in Alaska, provided showers for homeless men on the Bowery, and proudly served five years as the caretaker and head docent of the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage in The Bronx. He’s married to a Norwegian herbalist and lives part time in an octagon. He has two stories about Edgar Allan Poe in the magazine Rosebud.